Echezonachukwu Nduka: Hello Alexis, I am yet to find the right word with which to clearly express how I feel about having this conversation with you at this time. I think of words like uplifting, exhilarating; therapeutic. These words fit because every one of us, in every part of the world, is experiencing the specter of a global pandemic. Many have been adversely affected, and in many ways, our perception of reality has been altered. What I find most ironic about Covid-19 is that love and care – so best expressed through touch – is now best expressed by keeping a distance even from those whom you love. There were some disturbing projections from the Western media about how Africa would be so badly affected; there were projections that the streets would be littered with the bodies of dead and dying Africans. Well, that’s not happening and I can’t be more grateful.

How are you doing, Alexis? Has the pandemic affected your creative process in any way? On my part, I’ve had to deal with the reality of not being able to perform live in concerts as a pianist. Concert venues have been closed, and a lot of performances were cancelled. Readings were cancelled too. The only option has been to play virtual concerts, and I don’t like that very much. However, I still have my online teaching sessions and piano practice sessions. I have been able to do some solo and collaborative recordings as well. The bearable part of this whole experience for me is that while a lot of people were tired of staying home on lockdown, there was no such feeling.

When 20.35 Africa invited me to have a conversation with you, I found myself online, clicking away at your works. Then something happened. I realized, much to my surprise, that our works had shared a space in Jalada 04: The Language Issue, published in 2015. Reading your poetry has been a terrific experience for me. But now, I’m beginning to feel like I’m more drawn to listening to you read, many thanks to the recording Jalada has of you reading your work. Your reading has a calmness, an uncanny sort of calmness. There has to be something about how a poet’s reading holds potential for gifting an audience with clarity and a deeper emotional connection. This is especially true when one writes about language, about traversing its boundaries, and using its powers for expression.

Your poem, “Turmeric,” published in 20.35 Africa’s Volume I anthology is a brilliant example of the path this generation of African poets is charting with our passions, concerns, dissatisfactions and satisfactions. We are exploring wide-ranging themes, some of which are done through interrogating the self, the familiar, the personal. We tend to view the body through diverse lenses, examining its wide scale of sublimity and pain. I’m intrigued by the ending of your poem, where the speaker asks:

What if I, for some vague devilish reason, somehow grew sideways,

like this ginger rhizome here?

It makes me consider the question of choice, how we choose to respond to pain and the dynamics of power therein. There’s also this sad reality about ways in which people suppress their emotions. The closing line of your poem is a poser that underscores this point. Perhaps that’s what Tariro Ndoro’s poem “Asphyxia” does when the speaker says “believing their lies so we can sleep at night.” Turmeric also brings to mind Michelle Angwenyi’s “Old Things,” where the speaker unequivocally states “we pretend to be okay.” This pretense, which is a means of surviving through pain, is interrogated further in the concluding line of the poem where the speaker says “you are not dead, but you have never been much alive.” It shows the propensity of masked emotions to disintegrate in the face of enquiry. Consider Thato Chuma’s “A Long Sky,” which begins by stating “If women could weave their pain, it would be longer than the sky,” and goes further to negotiate possible means of survival. In the end, the speaker says “We survive, because our mothers survived.” The same can be said about Victor Ugwu’s “Fragile,” where a character forces orange juice inside her razor-torn thighs. That could be a metaphor for finding sweetness, or navigating through pain, which in itself is a means of survival. It shows the extent one can go to negotiate with pain, using the body as a conduit.

Do you consider any boundaries or grey areas while interrogating the body, or translating pain into poetry?

Alexis Teyie: When I was finally able to read – in January – the note you sent in September, I felt exactly as you said: exhilarated, and consoled in some unnamable ways. Thank you for your attention. Since my response comes well into the new year, I’ll ask if you’re part of the resolution crowd or the opposing camp. I have always turned my nose up at New Year’s resolutions, but this year, I have a little mantra or chant I’m relying on: a heart is to be spent. Where’s your heart at in these first few days of 2021?

I must bore my loves with how often I repeat J.D. McClatchy’s “Love is the quality of attention we pay to things” and Simone Weil’s “Absolutely unmixed attention is prayer.” I think this is how I reconciled the dissonance of care brought about by the Covid-19 pandemic and its accompanying social distancing. My focused attention is a prayer, its own love. Even so, as I said to you, I barely scraped through 2020 but while walking our incorrigible puppies today, the keen attention they paid to every little thing reminded me that joy/love grows like a weed, even when neglected and trampled on. I am glad that you had your teaching and some collaborations to keep you afloat amidst it all. And now that I know you’re a talented pianist, I find your piece in that Jalada Africa issue even more poignant. I wonder if you’d share any music you’ve been making/enjoying lately? That issue was very special to me because I was glad to see the team working with both audio and text. And now, even though we’ve never met in person, remembering that I heard your voice sometime in the past makes me feel I have a sense of you. You’re right about poems and readings: a poem read out loud performs a distinct magic. When I listened to your recording again, this time, I found “lost winks too” immensely moving. Poetry is deliciously pliant.

You are reading such wonderful writers (I’m chair of Michelle Angwenyi’s fan club). I’m glad to be interpreted as generously as you do. You ask about translating pain into poetry, about the body, and mourning. Last Christmas Eve, as is my macabre custom, I reviewed all the poets who died over the year. Early in 2020, Kamau Brathwaite left, then Eavan Boland, Michael McClure, Derek Mahon, and goodbye too to Miguel Algarín. The year before, Les Murray who wrote:

People can’t say goodbye

any more. They say last hellos…

I hear similar echoes in your work – grieving, savoring, letting go. I thought of both Les and Kamau when I first read your magnificent opening to “A Short Note on Departure Theories”:

The only way to defeat departure is to say goodbye & stay.

Say see you soon but sit still.

Ah, and of course, the line “Fighting absences with resonance is an unwritten law of sound” from the same poem was even more gripping.

For me, translating pain into poetry goes back to one of the proverbs I can’t seem to release from my last book, Clay Plates: shoka husahau; mti hausahau. I translated this as: the axe forgets; the tree does not forget. Linked to the epigraph is another proverb: kisebusebu na roho ki papo, which is hard to render but I went with, “to refuse or relinquish, yet one’s heart continues to want. Masking one’s eagerness with a false nonchalance.” These proverbs are a guiding light in my translation of pain into poetry. They help me say this: I’m faithful to my tragedies, and bashful about any longings.

The first poem I memorized, at 8 or 9, was actually “after great pain, a formal feeling comes.” I loved this poem to a point of utter embarrassment. Do you remember the first time you loved a poem to embarrassment? Tell me about it.

I love how your work as a musician threads through your poetry, and especially after 2020, I’m grateful for such gentle liminality. Frankly, musicians inspire a gritty sort of envy in me; I’ve always believed it the most magical of arts, composers and oboists especially! It can be a bit of a tedious question for a writer, but I wonder, why do you keep writing, still? Is this the same reason you make and perform music?

Echezonachukwu: I couldn’t agree more with your little mantra of the year; a heart, indeed, is to be spent. I cherish the idea of spending our hearts here and now. I suspect that this may have something to do with my consciousness of mortality. In fact, our commitment to spending our hearts here and now may very well be all the impetus we need as creative people on this journey of life.

I once was part of the New Year’s resolution crowd until a few years ago when I finally had to own up to the fact that I never kept mine past the first few months of each year, and therefore saw no reason to continue with the crowd. I killed that tradition. It wasn’t a question of self-discipline or the lack of it, but rather the discernment that my heart seeks the sort of freedom that transcends certain inhibitions and the regimentation of calendar dates and seasons. That may sound lofty, I admit. But that is the idea.

In these first few days of 2021, I’m exploring myself more, and doing all the things that move my spirit: listening to a lot of music, bonding with family across the oceans, burning scented candles, checking out men’s fashion online, reading poetry to the rising smoke from incense, and dealing with emails about my new book, Waterman. I have also been thinking a lot about my work in progress. Sometimes, I follow up on American politics and news to keep me grounded.

You ask why I keep writing, and wonder if it’s the same reason I make music. It’s indeed a question I ask myself once in a while. Writing, to me, has become a sort of engagement that reassures me of life and the beauty of imagination, while validating my experiences and that of others in our collective struggle to make sense of life in all its glories and shortcomings. I write because my thoughts are better expressed in writing. I love the art and craft of writing, of listening to and sometimes questioning the voices in my mind. And of course, I love the little sense of accomplishment that heralds each published work, or the genuine responses they receive. I write because I want to be read. The same can be said about my music. Applause from the audience may be all my heart needs to drive me back to the piano where I sit for long hours, practicing. But even if I do not receive thunderous applause, I would still play music. To make the scale even, I would also like to ask why you keep writing. Do you foresee the possibility of giving up writing in the future?

Thank you for your question on loving a poem to embarrassment; thank you for the memories this question brings to me. The first time I loved a poem to embarrassment was back in High School. I had read Gabriel Okara’s “Piano and Drums” and couldn’t get it off my mind. I memorized the poem and often imagined the sound of drums and a wailing piano. It must have been one of my earliest memories of experiencing how music could come alive in a poem.

You speak kindly about my poetry and how I manage to weave music into it. Thank you! The same can be said about your poetry with regard to language. I weave music into my poems, and you, your love for language into yours. Your dexterity with language, especially in those work where you weave Kiswahili into your writing, is astute. I see this in your poem “Msema Pweke Hakosi.” In the poem, you write “I’m not sure how to laugh in English yet.” In fact, the epigraph declares: “Euclid in Kiswahili is possibly Ugaidi.” There’s a clear approximation in the subtext. The poem has many words in Kiswahili. The same can be said about your book Clay Plate where you use many Kiswahili proverbs. Do you have any poems that are written fully in Kiswahili? I’d be excited to read them if you have. Your experiment with language in your writing brings to mind an idea I have often toyed with: all the works and walks of life have possibly been referenced in poetry. You find a home for geometry in “Msema Pweke Hakosi.” Here, poetry is perfectly fused with Math as you write about Euclid and Euclidian motions. Geometry in poetry! Now this reminds me of poets like Niran Okewole and Dami Ajayi who fuse medicine, particularly psychiatry, into poetry so beautifully. I see you travel from one language to the other in your poetry, skipping from concept to another, from Kiswahili to geometry. Do you sometimes bother about the multifacetedness of translations?

Alexis: I certainly agree with your view on writing – and music – as an engagement that reassures us of life, reminding us again of the immense beauty of imagination. My love R and I have been reading about how the haptic experience of photography is fundamental. I definitely feel printed images ground me in a distinct way; I feel them tell me: “Yes, we’re still alive.” And this is good, this grounding. I have an oddly specific vision of you on your piano bench. As a child, my father loved the D.H. Lawrence poem, “Piano.” I think of this poem often, and Gabriel Okara’s “Piano and Drums” too.

It is very affirming to hear you speak of “Msema Pweke Hakosi” and the home it makes for geometry. In truth, I am not designed for complex Maths, but I’ve read Euclid so many times, and perhaps without meaning to, I have created what is the fusion of poetry and Euclid. Perhaps you are right; all the works and walks of life do come home to rest in the arms of poetry.

On having poems that are fully written in Kiswahili, it is my ultimate dream to improve my craft so that I can write several books in the language. So far, I barely have a chapbook of Kiswahili poetry. Unfortunately, since I moved to Joburg, I stopped thinking/dreaming in Kiswahili and I now have this jagged, jumbled mesh of a language I’ve decided to make do with.

Tell me about Waterman. How do I smuggle it tax-free to Nairobi?

Echezonachukwu: The surest way to get a copy of Waterman would be to contact Griots Lounge Publishing, and it’ll be mailed to your location. I’m sure they’ve also got some distribution channels on the continent.

It’s quite interesting that you intend to write books in Kiswahili. What you said about thinking or dreaming in Kiswahili when you moved to Joburg struck a chord with me, and a poem by Victoria Adukwei Bulley in Volume 1 titled “Revision” came to mind. Its main theme is colonialism, but it’s also about music, language, and disruption. The poet writes, “I look for my language/still finding their hairs in it.” My language is Igbo. But there’s also Engligbo, which is a hybrid of English and Igbo. It has become one of the most commonly used expressions by Igbo speakers, some of whom argue mostly from an uninformed perspective that the Igbo language is somewhat insufficient because certain English words cannot be expressed in Igbo. There are other perspectives on that, and there are scores of published scholarly works on Engligbo as well. I have read Igbo poems, but I haven’t read one written in Engligbo. On a comparative note, I would like to know if it’s the same with Kiswahili. Is it common practice to mix Kiswahili with English?

Thinking of Bulley’s “Revision” gives a mental picture of you dreaming, and in that dream, you’re looking for your language as the persona does in “Revision.”

Alexis: It is magnificent that I can get a hold of your book at Griots Lounge. I’ll get in touch with them and give myself a gift for making it to another month, thank you.

Bulley’s poem got me good. I’d first heard of her work through Brunel, but never actually read any till the 20.35 Africa’s volume. It unglued me when I first read it. I remember loving the tongue-in-cheek of “two colonizers: one with / better weather, what’s the problem?” I like when a writer makes me laugh out loud. I also admired where the poem calls readers to compare the differences in names and to consider different versions of facts at the beginning of the poem. The linguistic nuances were fascinating. When I started writing longer work in Kiswahili, I discovered such a range of linguistic roots: Portuguese, too, and Chinese, and German, and Malay, amongst others. Like Bulley, myself, and you, there are so many of us with these inmixed vocabularies. Tanzanians mock us because most Kenyans can’t speak ‘pure’ Kiswahili; often we speak Sheng (that is slang with English plus other ethnic languages.) Engligbo sounds ticklish in my ear! Would you try making a poem in Engligbo? I’d be glad to read that.

I’m not sure how I would put Sheng on paper, but Rosie Olang’ and I are experimenting with this in our new imprint. It’s like song and dance to me. How does one pin this in print? I wonder if we must at all. Maybe you’ll choose never to write in Engligbo, and that doesn’t mean you’re not capable, or the language is lesser, or you have nothing to say…I guess I’m teaching myself that print is not the topmost in a hierarchy of art, and making. I like the wild, delicate power of words in the air, unfixed. I’ll try and revel in that more.

It’s a facile analysis that attempts to pull the threads of language, history, and literature apart. On the level of sheer reading pleasure, I am often drawn to poets whose poetry are wonderfully present, concrete, attentive to the now, as well as reworking, un-fashioning, de-memorializing our varied histories through their work.

– Alexis Teyie

Echezonachukwu: I’m delighted to hear about your new imprint, that you’re taking the exciting step of experimenting with writing poetry in Sheng. The idea of writing poetry in Engligbo holds interesting prospects. I think it’ll be entertaining, even though I wouldn’t write in Engligbo. The first challenge of writing in Engligbo would be its colloquialism. I’m afraid this colloquialism could possibly downplay the gravity of certain themes. For instance, consider a poem like “Uno-Onwu Okigbo” by Chinua Achebe which was translated into English as “A Wake for Okigbo” by Ifeanyi Menkiti, a poet in his own right. A translation of the line: “Egwu ebee na mbelede!” into Engligbo would be something like: “Egwu ebee suddenly!” or “Egwu ebee all of a sudden!” or “Egwu astopuo na mbelede!” which, to me, is quite funny even though the poem is a dirge and the line itself is the climax of the poem that refers to the sudden death of Christopher Okigbo. Pidgin English, like Engligbo, is colloquial, but it has become a more established language in writing and publishing. A good instance here would be Ezenwa Ohaeto’s poem “I wan bi President.” Since there are media productions in Engligbo, as is the case with Pidgin English, then I think it’s great to write and publish creative works in Engligbo as well. I am not an expert here. I believe linguists would know better. I’d like to talk about your poem “History is a loaded Gun” and how it interacts with history, providing several historical lenses through which we could look at language. I love this line,

There are small languages/pocket-sized, ready-to-drink languages…/

Now I wonder which categories Kiswahili, Igbo, Engligbo, Sheng, and Pidgin English belong to. In addition to language, I love it when history meets poetry. Your poem reminds me of Bulley’s poem which we mentioned earlier, but also Aremu Adams Adebisi’s “Clothing” in which the speaker traces histories and cross-cultural influences through fashion. As a trained historian, I believe you are exploring histories in your poetry as well. If that is the case, is it a deliberate decision? Please share your thoughts and preferences on the intersection of history, language, and poetry.

Alexis: I wonder about the idea of colloquialism compromising gravitas. I tend to bristle at overwrought pathos, and I find casual tragedy or beauty easier for me to assimilate, like some feelings must only be approached obliquely. You do give a perfect example with the Achebe poem. That said, I suppose translators have to be consummate poets because they must convey the spirit without a one-to-one conversion. For instance, maybe you replace the “suddenly” in that line with a sound of exclamation instead? Anyhow, I find translation only marginally enjoyable, but I compulsively translate little sayings, adverts, ingredient lists. The largest project I did was translating the Communist Manifesto to Kiswahili and it definitely unhinged me, ha. Have you tried translation? I’d imagine musicians are used to this alchemy, working across sheet music and their instruments – is this true for you?

What a line to pick out from “History is a loaded Gun.” I was reading your poem, Transition last week – is this included in Waterman? I keep returning to this line: “Who owns language? Native speakers or aliens & newcomers to the tongue?” It’s got me thinking of the wonderful Clifton Gachagua’s poem, “a long dance”:

What I’m considering is the simplicity of the words, their Greek and Latin roots. Here I curse that while other roots exist this is where I must come to. So, the words, their meanings and sounds, especially on my tongue, which carries the th and the dh as the same sound, the g and k as if they are related, the s and c as familiar cousins. I don’t even know what the w sounds like because I spell it as I see it and not as anything phonetic.

when my mother first spoke to me in Sudanese Arabic and I replied in sheng I wondered if we were ever going to learn how to love each other.

I think also of Nour Kamel’s “Other Ways of Saying” in Volume 3 of – bless their hearts – 20.35 Africa’s anthology series. Kamel writes:

ya nihar azra2

oh blue day

from sacre bleu

meaning

the french were here

…

mind chokes on

two words (at least)

and wonders why

nothing

ever comes out too good

You ask what my thoughts are on the intersection of history, language and poetry. Like Kamel, like Gachagua, like many other writers, I think through family, national and ecological histories in my poetries. It’s a facile analysis that attempts to pull the threads of language, history, and literature apart. On the level of sheer reading pleasure, I am often drawn to poets whose poetry are wonderfully present, concrete, attentive to the now, as well as reworking, un-fashioning, de-memorializing our varied histories through their work. I admire Maaza Mengiste, Jeniffer N. Makumbi and Yvonne Odhiambo particularly. And some of my favorite writers in the last 3 anthologies– such as Nermeen Hegazi, Dalia Elhassan, Gloria Kiconco, Lydia Kasese, and so many others, are crafting sensitive, gasp-inducing ways to expand what is included in “history” and deepen the unique languages we have available to us. These writers dwell mostly on poetry as archive, as a subversive, anti-canon way of writing our lives as we see them, in ways we delight in: beyond long manuscripts approved by gatekeepers; outside reading fees and prestigious prizes. Our focus is on how to capture this moment as truthfully (not necessarily accurately) as possible. I feel this archive, counter-canon, in small reading groups, in impromptu performances in our little flats, through our blogs, TikToks and IG stories. With histories as manipulated and unevenly available as ours, we have the wild futurist possibility of unlearning and rewriting received knowledge, and the associated radical faith to shape what is, and what follows. This daring is a gift. It is as difficult as it is good to be working as an artist in these times. What are you most excited for?

Echezonachukwu: These days, I am most excited for the privilege to perform and record music by composers of African descent most of whom are not very much known yet or considered mainstream in the classical music tradition. Works of such composers rarely make it to concert repertoires of famous performers, but that is gradually changing and I’m happy to be able to witness this shift. There’s an artistic fire that keeps burning in my spirit, giving me new dreams and the impetus to create even when I don’t feel like it.

You translated “The Communist Manifesto” to Kiswahili? Now that’s impressive! In 2015, I took part in a translation project that became a poetry anthology of world languages edited by Marlena Zimna. I translated four poems by the Russian poet Vladimir Vysotsky into Igbo. I have also translated Igbo lyrics of art songs by some Nigerian composers into English in our concert programs for the benefit of diverse audiences. Amongst other lessons, I have learned that language can be malleable yet complex. The multifacetedness of translation makes it somewhat tricky to navigate certain texts while striving to retain authenticity, especially with regard to the author’s intention. I suspect that I may have viewed the Achebe example from a simplistic perspective. Nonetheless, I still look forward to reading creative work, poetry or prose, in Engligbo. And yes, “Transition” is included in Waterman. It’s the longest poem in the collection. Ah, that line! The ownership of language is possibly a cultural and philosophical question that can be argued from all sides, and quite frankly, how would a definite answer benefit anyone?

As a trained musician, I am used to the alchemy of working across sheet music and the piano, but also of translating certain emotions ranging from melancholy to extreme rage on the piano during live performances or recording sessions. Certain compositions require the musician to transfer emotions to the keys in such a manner that they become electrifying enough to connect with the audience.

It has been such an interesting conversation with you Alexis, and I wish we could go on and on.

Alexis: Thank you Echezonachukwu! I’ve enjoyed these moments of stillness reading from you, and writing back. As you say, it would be far too easy to keep going once you find a kind, thoughtful correspondent. Thank you again.

I’ll steal into Rosie Olang’s social media accounts once in a while and follow your performances as you share them. It is magnificent to connect with and share composers who may otherwise have remained forgotten. R and I are keen to animate more archives, especially of African (women + queer) artists through our upcoming projects with Magic Door. I’ll keep you posted.

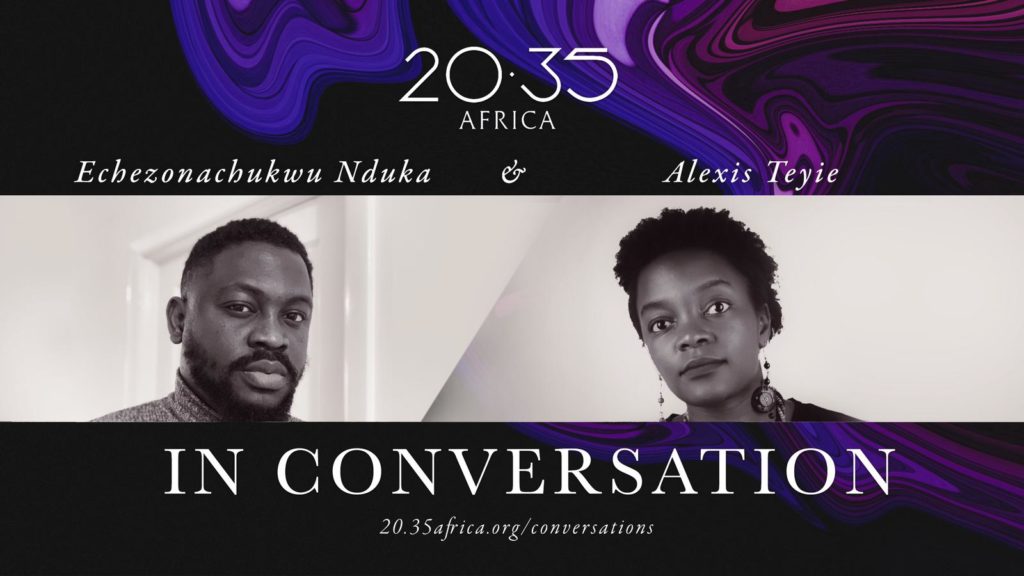

Alexis Teyie is a poet, and co-founder of Nairobi-based literary magazine Enkare Review and imprint, Magic Door. Alex has co-authored a children’s book, Shortcut (2015), and published a poetry chapbook Clay Plates: Broken Records of Kiswahili Proverbs (2016). Their work is also featured on Down River Road, A Long House, LitHub and anthologies by Jalada Africa, Short Story Day Africa and Routledge among others.

Echezonachukwu Nduka, poet and classical pianist, is the author of Chrysanthemums for Wide-eyed Ghosts (Griots Lounge, 2018) and Waterman (Griots Lounge Publishing Canada, 2020). He holds a BA in Music from the University of Nigeria, and an MA in Music from Kingston University London, UK. His literary works have been published in The Indianapolis Review, Kissing Dynamite, Transition Magazine, Maple Tree Literary Supplement, First Wave: A Beach Bards Anthology, 20.35 Africa: An Anthology of Contemporary Poetry, among others. His writing often centers on memory, music, faith, history, and the quotidian. He currently lives in New Jersey, USA. More of his works can be found on his website.