Àkpà Arinzechukwu: This morning I woke for my Sahoor and was moved to read Surah Yusuf 12:13, wherein Jacob tells his sons who were asking him to release Joseph to them, “Indeed, it saddens me you should take him, and I fear that a wolf would eat him while you are of him unaware…” and am reminded of this poem of yours published on 20.35 Africa, “[This Morning, in the Mirror].”

Even death loved something about him

to want him from us. Something the others didn’t have

or death just takes – like a lottery, random picks.

Honestly, what bothers Jacob is that death could love his favourite son more than he could. Jealousy born out of possessiveness made him kick when his other sons sought his permission to take Joseph away with them. But Jacob is like Mahmoud Darwish writes in Mural, “It’s the luck of the traveller that / hope is the twin of despair” – he knows that death wants what it wants, and he goes ahead to gamble with despair. If death harvests from a field, does the original owner go home to cry, or does the owner count his loss, name the field “desolation,” and sleep in the fallow without waking?

You are a writer I admire greatly, so I am grateful to 20.35 Africa for making this conversation happen. Pray tell, if poetry is where we come to feel, how much of feeling goes into your writing, and what is your process like?

Henneh Kyereh Kwaku: I will do anything to escape any questions about my writing process. I may need to be more smart to articulate it, or my writing process needs to be more coherent to put it into words.

I can’t disagree with your take on Jacob and his sons, but if death loved Joseph, then it was not enough; at 110 years, it would eventually be. I am saying what we already know – love or not, manifests with time. It is love that leads us to enter your work now. You conclude your poem “Banach-Tarski/Suddenly” with these opposing lines:

Fill a boy with longing.

Bless a mother to sleep well tonight.

Longing and rest are two opposing ideas, except when longing for rest – which is still work and counters rest. Longing is “difficult” work, whether for a lover, a God, or an answer to a prayer. For me, longing is not just desire; it is also “waiting” and “hoping,” and these are complex things that sound very friendly. As a son who is barely home lately, & by home – I mean my mother’s kitchen, when we talk in the morning, it is our act of hope that each of us has not been loved so well by death. Rest can also be “death” or, to phrase it appropriately, death is rest. This deflection and reflection – thinking on the page – is my writing process, and is chaotic. Now, tell me about your process.

Àkpà Arinzechukwu: I like that you pointed out that death is rest. The Igbos say, Ezumike adịghị na ndụ, meaning there is no rest in life. One Sunday, I learnt from my mom that her cousin had died. The day became slow and uneventful. There were activities: my aunties cried, and the men washed and clothed the corpse. I was beside my mother, reading and thinking about poems to comfort us. I like to think of poetry as a prayer. It is a prayer offered to the world, or precisely to the void – the vast expanse of earth.

Uncle Walter went to rest; not even our love could keep him busy a little longer. That night, we all said a prayer for him. Searching the internet, I came across Jeremy Karn’s “Sickle Cell Is the New Tribe,” which is a prayer for someone named “Bijoux,” and the lines messing with me are:

there will be someone who will set god down in a dark room and

interrogate him about his likeness

or say maybe God has sickle cell like you

And in this is the hope, the consolation poetry, like prayer, offers us. Maybe death loves us all, some with greater intensity, some with overlooks long enough. Because in the moment of losing someone or coming to the realisation you might lose someone, you begin to question God, which is synonymous with questioning love. If my love can’t save them, let us talk to God. Denial.

About that, I deny having a writing process. I start with love. I approach writing with love, a banal sentiment. I want to say I love something and make you see how much. But love centers loss as well, so I read the Quran, the Bible, the Tao Te Ching, some Kevin Young, Anaïs Nin, Kahlil Gibran, Essex Hemphill, Alan Bennett, Sandra Cisneros, and a few others, depending, just to feel worlds and words go through me. I don’t even need to read all of them. I just have them by my side, looking at them and thinking about how to reach them. Think of it this way: I carry a shrine in my head of the literary greats and God supreme.

Did you know hair is spiritual to the Igbo? Who cuts our hair is whom we share a spiritual connection with. I have not cut my hair since the last time we spoke. This is the last thing to do during mourning: to shave your hair in respect to the departed, for the living to keep living. Do you have a similar thing in Gonasua? Does your hair keep you close to God, or is it a departure or a rebellion?

When I first encountered “A Short Note on God, Loving, Leaving & Living”:

God’s PR is really thick, says a word & all his Children

In their languages respond, Amen!

I wanted to email you immediately to talk about mango dropping and God’s innate secret of the world. The poem is about performing for God. How much of our living is performance?

We all know what we want from God and our ancestors, but not knowing what they want makes it difficult to please them, even in death. So, Kwaku, how much of such performance exists in your craft, and how much freedom do you seek? What is the work of a poet who is tired of grieving?

What’s next after we have survived a thing? I mentioned that love centers loss. I meant that one could not write a straightforward story about someone leaving without approaching love. It is a stretch.

Considering how we have both looked at desires, our desire to appease the dead makes us shave the living part of us for them (which is the hair). We want God to want us. What do you want from a poem, from prayer, from God, from living? We could all be one disaster or another waiting to happen, but we don’t want death to want us. Is this not ironic? Have you ever wanted to scream but felt restrained? Zafrina Nyawira Muthoni Njenga, in her poem “The Silencing,” notes there are three types of screaming: “the scream of metal, the scream of agony and the scream of silence, in that order.” Do you make sense of this? To be so loud you can’t be heard? To want and not be wanted? To tell and not be believed? Bringing us to this, what does a poem, like God, want from us?

Henneh Kyereh Kwaku: I am sorry to hear about your family’s loss – the last time I was home in January, I attended the funeral of my cousin’s mother. But I returned with somewhat good news, anticipation for future nostalgia, and intense “I miss yous.”

The thing about God and love is that – we are all children of God and Asaase Yaa (the mother earth) and so who are we to say no when God or the Earth decides to bring their children home? Are we not selfish, too, to want to keep kids from their parents? Sometimes, these excuses help us move on when we lose the people we love. I am yet to move on from many losses and I have accepted many losses, but one of such is “A Short Note on God, Loving, Leaving, & Living.” I would like to say something clever about living as a performance like the world is a simulation and there’s a higher being somewhere controlling our actions and inactions. But that is not me – there is something about intentionality that makes it sound/look like a performance and there is beauty to that. That is why people pay vast sums of money to see their idols perform. That beauty is necessary in a world like this or any other.

The last time I grew my hair, it was because I wanted to. I had grown accustomed to cutting my hair every two or three weeks, but I let it grow for about six months this time. It was an exercise of freedom; it was not, intentionally, a thing of spirituality or tradition. But, eventually, I had to cut it because someone who cared about me and whom I respected did not like it and I did not feel I had the voice in the moment to bring them to my understanding. But in the future, I would twist or braid my hair as a thank you for all I have done for myself, even if for a couple of days. Is that not also a performance?

A poet tired of grieving is also a human tired of grieving. We cannot afford to lose our humanity. It is what makes us poets. A human tired of grieving may break and, that is fine – it is only worrisome when we cannot rebuild ourselves after breaking. I have been broken and I have hurt myself in several ways. There are parts of me I keep rebuilding because sometimes they take a shape that doesn’t appeal to me anymore. Sometimes, that is what I look for in poems, the ability to shapeshift, to revamp into something different.

Being unwanted is a disaster and I have recovered from many of such experience. Some people don’t understand that to be desired is an integral part of being loved. Jesus knew he was loved, but certain things always stood out for him: the perfuming of his feet, the many kisses, even the kiss that betrayed him. I love you could also mean I will kill you when misinterpreted – the root word for weed & love are the same in Bono – dɔ. When I weed you, will you survive?

Àkpà Arinzechuwku: Kwaku, how are you? Recently, I translated Dami Ajayi’s The Anatomy of Silence into the Igbo language. This was hard because silence scares me. Sometimes I fear keeping quiet would make me forget who I am or where I am headed. I fear being lost, and silence affirms that. I guess what I am trying to ask is, what are you afraid of, and what are you trying to save?

Henneh Kyereh Kwaku: I don’t consider it coincidental that you asked me that. I have always had a weird relationship with fear. Since December 2022, most of my conversations have revolved around this topic and I remember tweeting about recalibrating this relationship. Whereas some people may be propelled by fear, it cripples me – it nails me to a cross until I find a way out. I fear many things, such as (flying) cockroaches, most crawling animals, and dogs that look like they can tear me apart. I am afraid of the many possibilities of my aliveness. How does one get down from the cross that fear nails you to?

Àkpà: I wish I knew the answers to things that plague me. This inability to know is another fear of mine. It is why I write, to know – to understand some hidden things or emotions. The Church of Poetry has been, to an extent, a balm to me. I was hurting and determined to get some healing, and having a platform where I could talk about poetry with people who love poetry was important to me. I always looked forward to it.

I am in Calabar right now. When I came here, I was in the car of a military officer. He had a chihuahua that I didn’t see before entering the vehicle. And when I sat, he jumped right onto my body, and I froze. I thought he would attack me and thought of jumping out, but he just licked me. I was told the dog liked me. His name was Captain. I overcame that fear of facing him and we became friends. Now, I don’t want to imagine meeting one who is not Captain, one who bites me instead of playing with me. It is the same way I don’t want to imagine what I would do when I lose a loved one. Your poem, [This Morning, in the Mirror], breaks my heart. It makes me interrogate grief in a way I do not wish to. It makes me want to know who you are writing for and how you came to poetry. Please tell me.

Henneh: Your encounter with Captain reminds me of a proverb and something my class two teacher, Mr Besori, said. The proverb goes: If the dog will not bite you, it will not bare its teeth at you. Mr Besori would say to ask dog owners who claim their barking dog would not bite if they are in the dog’s head. That is the same question I pose to people (in my head) when life is coming at me with bared teeth, and they say, don’t worry. It is true that, like dogs, life sometimes just gets excited without harmful intentions. But how can we know when we are not in its head? I wish I had a better answer, something you can rely on when you meet another dog.

The poem you speak of is very close to my heart – it is written for an Uncle who died too young or died when I was young. I wish he had not, or even if he was going to, I wish we could tell when he was sick that he would die, but who is in death’s head? Speaking of death and grief and dogs, in your poem “After Suicide” the third stanza reads: “At night your dog kept barking, / we thought it was learning to accept the heat.” We too believe dogs and cats can tell when their owner is about to die, and that they can also see the dead. This barking here is not one of an intended attack but an acknowledgement of a presence and a question: Why have you left me here? Outside of a poem, how do you interrogate grief?

Àkpà: Some animals are indeed discerning. A dog or a cat can perceive a conception before anyone in the family and sense the Angel of Death at the door. It is why my people do not dismiss the wailing of a cat or a dog as mere “animal traits.” There is a meaning in there. In such an instance, the poet must discover what troubles the animal. A poet petitions their soul or body for an answer and comes out with a poem. To answer your question, I have to ask myself the things I am without prayer. Nothing. This is because I know that prayer is a gesture towards the body. We are always reaching for the insides of us as much as the inside of the world. What I mean to say is that humans will always go looking for poetry because it is the one way to make sense of our world. When the person who inspired the poem you mentioned died, my family turned to prayer. We asked the whys and still told God to let his will be done, and I wrote a poem I thought was me accepting the fact that God’s will has been done, that the loved one will not come back nor suffer anymore. I want my poetry to do for me what my visits to therapists over time have not been able to achieve. So, this is why I started with poetry, hoping to end there. There is no outside. It is how I navigate life now because grieving is only possible in my thoughts and in the hopelessness of those thoughts. Recently, I read The Inhuman: Reflections on Time by Jean-François Lyotard. In cajoling philosophers about their grandiose antiques towards posing questions perceived to have no answers, Lyotard writes, “After the sun’s death there won’t be a thought to know that its death took place.” This is true about the dead. Knowing that they have no thought about their demise, poetry becomes an avenue to speak to them to make living easier. Whether a response comes or not is a matter of another poem. It is a ritual – one I cannot be outside of. Do you understand me? How is it for you?

I want God to save me, but when I ask the same from God about my country, I do not stop to wonder who God is saving my country from, but as a ritual, I keep doing it.

– Àkpà Arinzechukwu

Henneh: I agree with you to an extent. I look to poetry often to understand what seems abstract. & sometimes to abstract reality – whichever serves me in a moment. When we acknowledge poetry as life, we must be careful not to conflate what could become as what is. Poetry is not confined, it shapeshifts, metamorphoses into other things, including life, and often, even the poet can lose control of the poem. What I mean is poetry is all that you say it is but not limited to that. A poem can become a placard, a dead son singing odes at dawn, a child that will never be born, a bullet, a prayer, or a metaphor for life – but poetry itself, even as life, is outside of life. In interrogating grief, which can be a poem or an essay that will never be finished, I do not hold back. I cry or call a friend or a sister, someone I assume cares about me and may be able to unload some of my burdens.

Àkpà: On the 29th of January, A’bena and I were on Citi 97.3FM to talk about our work in translation, Muqabalal, and the Church of Poetry. It occurred to me then the grace I had to talk about myself how I wanted. Martin Egblewogbe of the Writers Project of Ghana had asked me how I would like to be addressed and I knew then that I would be sharing with them an unpublished poem I wrote interrogating a father’s absence.

Where I come from, instead of “Whose child are you?” you get “Who is your father?” My poems are all those silences, absences, negligence, et cetera. It is the same as yours. Your chapbook comes to mind. You are talking about Ghana, but you are praying. It is something I always admire about your work. I don’t know how to write about my country without self-destructing. I want God to save me, but when I ask the same from God about my country, I do not stop to wonder who God is saving my country from, but as a ritual, I keep doing it. West Africans have all these struggles bothering us, but we approach these subject matters differently. It only saddens me that the critics of Nigerian poetry, for instance, are unimaginative. It is why the actor and playwright Alan Bennett writes that “critics should be searched for certain adjectives at the door of the theatre.” For us writing about hunger, poverty, queerness, prosecutions, etcetera, we get termed as “pandering to a Western gaze,” navigating “poverty porn,” or, as a Nigerian Twitter user in the USA criticized Adedayo Agarau, that “they” as readers are tired of reading about EndSars poems or any poem at all sprinkled with misfortunes, that if they needed such matters, they’d consult the news. It makes me wonder what the role of poetry is in the contemporary world. Who are we writing for? Is this still an avenue for self-expression?

When I read the poem about my father on the radio, someone texted me and asked what I stood to gain by sharing such a poem. By being present in the world, we get to write about it, and the experience thereof inspires what we choose to write about. Is it not ludicrous that certain people want us to sacrifice our experience to please them? The Igbos say, Onye sị n’ofe m adịghị ụtọ sie nke ya – whoever claims my soup is not delicious should make theirs. Is this a concern for you, too?

Henneh: I am reading The Poet’s Companion by Kim Adonizio and Dorianne Laux and in the first chapter they say, “…we begin [the poem], by looking over our own shoulder, down our own arms, into our hands at what we are holding, what we know.” Then, “no one can call himself a poet unless he allows the self to enter into the world of discovery and imagination.” When the poet in Nigeria, like the poet in Ghana, in Congo, the poet in Jamaica, or even the poet in America, looks over their shoulders, what do they see? The answer is right there. They will start with what surrounds them, before entering the world of discovery and imagination. The critic fixated on “poverty porn” is from a place of privilege and lacks the rigorousness of a well-informed thought. I cannot write about snowy winters when I live at Kwaprow, Cape Coast, where my room floods when it rains – I will start from there. I will start from Drobo. I will start from Gonasua. I will start with Hohoe. I will start with Orange, before “wonder.” And if that is “porn,” then every poet engages in some kind of “porn.” To write of Ghana is to write a love poem to my country – my family, friends, and even the people I do not like. It is a love letter to myself. Sometimes the poem and the letter are also prayers, and praying, like writing a poem, is an act of vulnerability. You don’t go to God high on ego; same for the poem – you humble yourself so it shows you the way. In Revolution of the Scavengers, I am as lost as everybody, but I am also asking questions, most of which I will find no answers to, but I am willing to make a fool of myself in love. It would be disingenuous to say that sometimes I don’t care about what others think of my work – I do, but I also remember to look over my shoulders, down my arms, and into my hands.

Àkpà: “You don’t go to God high on ego” is my new mantra. Thank you for that insight, Kwaku. I too would like to write about flowers hovering in the sky, the sawdust of my childhood, but it is as Camille Dungy writes, “I was trying to write about beauty, but grief won’t stay away.” I read a lot of criticisms about what an African creative is supposed to do and not supposed to do, which makes me ask – What truly is an authentic African story? African literary gatekeepers know what I don’t. Do you have an idea of this? Today, I started playing with a stupid memory of me with a friend and ended up with a poem about their death. Reading it now, I feel un-African or whatever the critics mean. I am re-examining specific arguments I had in the past. I have realized that as a creative, it is imperative to protect myself from armchair critics in Europe and North America who want to use me as a bridge to satisfy their needs. But except the goat wants, the Igbos say, it can never be forced to eat yam. Another person’s reality is not mine.

This might sound easy but for some others, it is not. It is already difficult for the writer battling imposter syndrome; receiving such criticism might feel like a confirmation of their fears. They become overburdened by their need to create, to reaffirm themselves as a writer. Then comes the feeling of inadequacy. Some younger poets gave up writing because of this. Have you ever been in that nest? Have you ever felt like you were indeed not called for poetry?

Henneh: As long as there is no single way to be African, every attempt to pigeonhole the definition of an African writer will fail. All the many versions are valid. Sometime in January 2023, I attempted to write toward joy (beloved, here’s my confession), I wrote the saddest poems I have ever written. But the other truth about those poems is that there are bursts of joy all around them, and such is life – joy here and there, but also despair. As Nikki Giovanni says of writing love poems, “being a writer or a poet takes a generous spirit and a willingness to make a fool of yourself.” There is an Akan proverb that says nobody has ever grown, but everyone has been a child. And because we often associate growth with wisdom, this is what I think of myself – I have never been wise, always a fool. But in truth, the foolish man knows more than everyone thinks he does and is willing to learn more. I am still a young poet and my freedom is in my foolishness, which allows me to embark on the most absurd of projects without seeking approval from anyone. If other young poets can, they should go as wild as they could and someday the world will come to watch them in the circus they made for themselves. People have said whatever they want about my work, but who cares? We all will die soon anyway, so why not be as weird as possible? Go wild! Go rogue, sexy, and godly! Do whatever you want, your audience will meet you. But, of course, I do not say this to mean that criticism is not necessary for art but don’t let it stop you from what you are doing. If we live long enough, we will realize that every nut will find its bolt. Do you ever feel like you were indeed not called for poetry?

Àkpà: Your words remind me of “Requiem” by Bei Dao, wherein the speaker muses that:

to be lost is a kind of leaving

and poetry rectifying life

rectifies poetry’s echo

Are you aware of the theory of Negative Capability in literature and psychology? John Keats first proposed it in his letter of 1817. He writes that the negative capability is a writer’s ability, “which Shakespeare possessed so enormously,” to accept “uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.” This theory perceives that a poet has to abandon self-consciousness, logic or science and open themselves to all the mysteries and uncertainties that abound in the universe. When one writes, it is to discover, just like you have said previously about setting out to write about joy but ending up writing the saddest poem you’d ever written. In Why Poetry, Mathew Zapruder, examining his life in tandem with this theory, writes that it is “intensely liberating as a writer to realize that the poem is not a place to be categorically convinced of anything.”

Zapruder also establishes that his reason for ending up as a poet, he thinks now, is his ability to jump around from ideas, which a previous head of the department warned against. You see, Kwaku, I am a poet who moonlights as a fashion designer, essayist, a witness to other people’s joys, shoemaker, academic, translator, and teacher. I am always jumping. Sometimes, there are doubts. Such things abound. A few years ago, I vowed never to write one more poem because I felt I didn’t have it in me. Since we started this conversation, I have been travelling and going about other projects of mine, but never poetry.

In psychology, negative capability is proposed to be a factor that contributes to problem-solving used in some aspects of the psychotherapeutic process. So, despite my uncertainties about poetry, like Zapruder, this is why I have come to this. There are several things I need help to do in my essays. Essays involve a certain kind of intactness. In fiction, the line between magical realism and imagination is often blurred by conventions allowed in that world, whereas in poetry, it is total freedom. I could be talking about my dad in the first stanza, his childhood in the second, and a cat’s funeral in the last.

I just wrote a poem for the first time in two years. In the absence of poetry, I took to journaling. While journaling has been good on its own, it was when I started writing poems again and figuring out this negative capability that I was able to dig into my subconsciousness and finally reach that place which I didn’t know was possible.

So, yes, you are right. Younger poets should dive right into uncertainty; abandoning logic is what makes them a poet. Did you know what you were about when you wrote “Someday I’ll Love Kwaku Kyereh”? You recently told me you were writing a new poem. Would you mind sharing a draft?

Henneh: In Ama Asantewa Diaka’s poem “And I’ve Mastered the Art of Receiving Handouts Because I Come From This Place,” she offers us a peephole into the kind of love she wants, that most of us want. Here’s an excerpt:

I want a love

that doesn’t require me to be ridiculously multifaceted

in order to have a fraction of an equation at being equipped for survival

A love that doesn’t wait for another suitor to sing praises of my genius

before recognizing my worth

Or worse, only after I’m dead

I am hungry for a love my country cannot afford,

the way white lusts for a backdrop to outshine

I offer Ama Asantewa Diaka her flowers. I am in no great position, but I recognize her worth and sing praises of her genius wherever I am – wherever literature is. I am familiar with the elegiac nature of the poem because I am familiar with the country she speaks of – Ghana, which is also a metaphor for many other countries. I, like Ama, have only known love that “require[s] me to be ridiculously multifaceted / in order to have a fraction of an equation at being equipped for survival.” Only last night, in conversation with my friend and Ghanaian writer/journalist, Anakawa Dwamena, he said, “Sometimes you meet someone, some child in this country, and you know that this country has done nothing for them – no proper education, no good healthcare – nothing, just their existence.” It is pitiful how we are expected, by default, to love and be “patriotic” to a country that will sell and murder us without any provocation. But love is also the sin of poetry. Logically, none of us should love these countries. But can we not? Have we not written of these countries as we would a lover that just left our bed? But you see, contrasting what Zapruder says, even when the poet has not aimed at it, readers leave a poem with some sort of conviction, a spark, a flicker – something that cannot be named. And that is how revolutions happen, unnamed until after the upheaval.

I am happy to hear that you have taken to journaling, something I wish I could do. Perhaps, my life is not as interesting. I try, and I forget; I go days without writing a word. However, I still keep journals and love returning to them because retrospection is always nostalgic. The poem, “Someday I’ll love Kwaku Kyereh,” likely started from a quest to write a love letter, more of a commitment-to-the-self letter – from the past to a present and a future Kwaku. But the truth is that even the past sometimes needs that same commitment. In the original version, the last couplet reads:

open yourself to the wind, let it carry you –

there’s a reason this wind blows in one direction.

I let the poem carry itself where it wanted to go, and we are here now. This is a draft of the second stanza of a poem I’m working on, titled “Dixcove”:

- The Girl

Without the dead, a cemetery is merely

cavities collecting rain for the earth. Here,

This hill, Golgotha—still holds ancestral bones,

of girls, boys, men, women—a living girl’s blood

holding the walls together. Golden ornaments

matching her skin; a man,

once the chief of his people.

I am still trying to figure the poem out, but for now, this is where I am. Tell me what you are working on and if you can share something with me.

Àkpà: It might interest you to discover that I have been up to no good. I have been travelling, reading, and preparing to come to sit with you this fall. Ghana is calling me now, so I am also writing towards that thirst because I just survived the tsunami that is my mental health. Poetry, to me now, functions as a postcard. I am always writing and sending them to A’bena. Here is an excerpt:

Look at the sky, A’bena,

I caught in a bottle

all our planetary stars.

They’ll illuminate your nightstand,

& guide your dreams towards innocence…

Postcards remind me of endings, which is one of the reasons we send them – willing our memories to the people we love, with the hope they keep tabs on where our journey ended for us as other ones begin. And to end this conversation, here is an excerpt from Esiaba Irobi’s Jane Bryce, “Jane, God gives us the first line, / then, / we are left to our own design…”

Thank you for your correspondence, Kwaku.

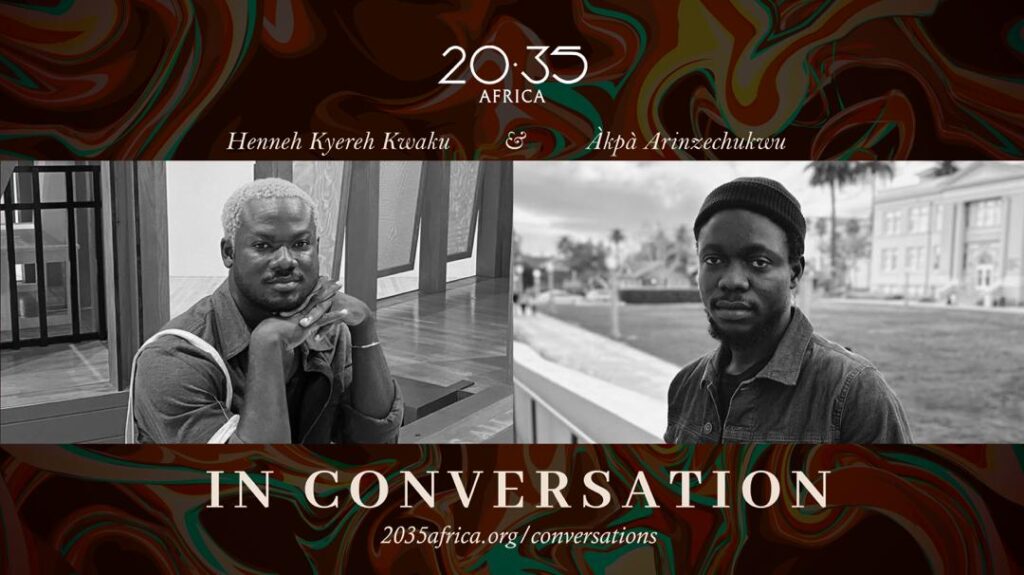

Àkpà Arinzechukwu is an English Grad Fellow at Chapman University. A 2023 Oxbelly Writing Retreat Fellow, and a winner of the 2021 Poetry Archive Worldview Prize, a Best of the Net nominee, Pushcart, and Geoffrey Dearmer Prize, shortlisted for the FT/Bodley Head Prize, and a finalist for the 2020 Black Warriors Review Fiction Prize, his works appear in Kenyon Review, Adda, Transition, Prairie Schooner, The Nation, Poetry Review, and elsewhere. He is the curator of Muqabalal, a bilingual conversation series, co-host of Muqabalal’s Poem-a-Day in Translation, and the Church of Poetry.

Henneh Kyereh Kwaku is from Drobo/Gonasua in the Bono Region of Ghana. As a “saito” scholar, his work explores Bono/Akan semiotics and onomatology, faith, language, and applied art in health education and communication. He is a Library of Africa and the African Diaspora (LOATAD) alum and has received fellowships from Chapman University. He is the founder and co-host of the Church of Poetry on Twitter Spaces. He’s the author of Revolution of the Scavengers (African Poetry Book Fund/Akashic Books, 2020) and his poems/essays have appeared or are forthcoming in the Academy of American Poets’ A-Poem-A-Day, Poetry Magazine, Prairie Schooner, World Literature Today, Air/Light Magazine, Tupelo Quarterly, Poetry Society of America, Lolwe, Agbowó, CGWS, Olongo Africa, 20:35 Africa & elsewhere. He shares memes on Twitter/Instagram at @kwaku_kyereh.